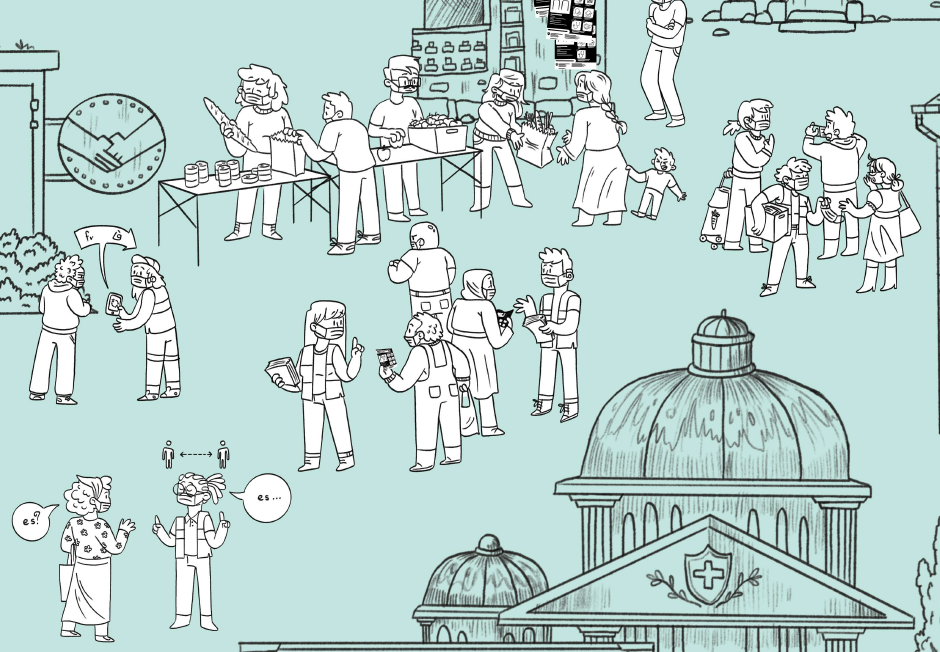

Food banks

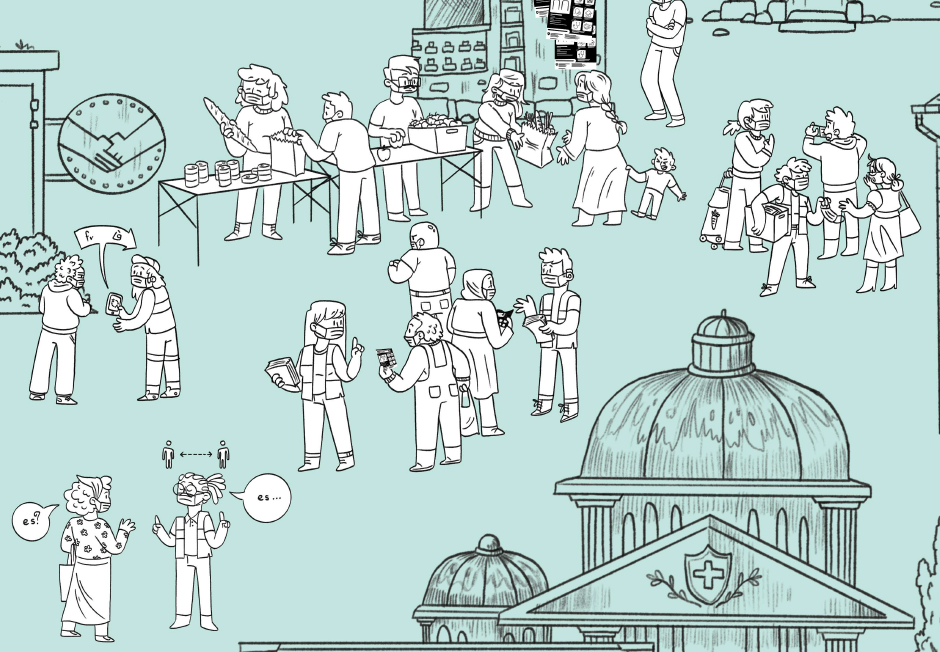

The number of people needing help to buy groceries increases drastically during the pandemic – national news media begin publishing images of long queues at food banks already at the start of the crisis. NGOs and civil society organizations take advantage of these situations to distribute multilingual information (circulars and other materials) as well as hand sanitizer and masks. These settings are also very useful for answering frequently asked questions about preventive measures or employment-related issues.

Federal Office Of Public Health

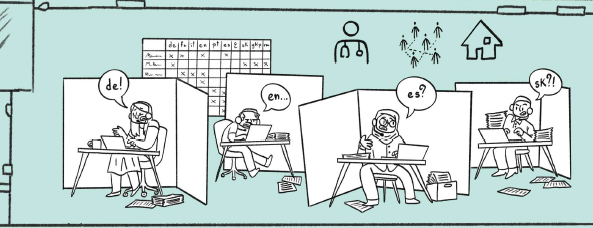

Soon after the national coronavirus campaign is launched, several NGOs and migrant-language media criticize the policy of communicating solely in the national languages and English. To be sure, the FOPH has already commissioned additional translations, but these can’t be produced quite so quickly, as a selection of what to translate must first be made and translation services organized. In particular, the key questions concern the content to be translated, the specific migrant languages to be chosen, and the language service providers capable of delivering the translations. The target languages are selected not only on the basis of experiences made in previous campaigns but also with reference to the latest statistics on language groups and asylum seekers in Switzerland; needs communicated by NGOs are also considered. Although finding professional translators for uncommon languages like Tibetan isn’t always possible, some campaign materials are produced in up to 26 languages, in easy-to-read language and in sign language. Close collaboration with the federal language services is essential throughout the crisis, and language professionals in the Federal Administration receive phone calls and e-mails demanding expedient translations of the latest campaign products almost on a daily basis.

Translators outside Switzerland

Translators working outside Switzerland not only have to cope with high workloads, time pressure, different time zones, and technological challenges – they must also familiarize themselves with Switzerland’s rules and terminology. Depending on the country, they’re scarcely allowed to leave their homes, and the extreme restrictions on movement increases their distress

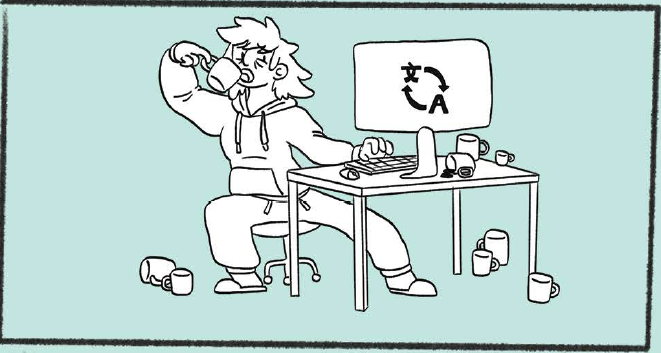

Independant translators

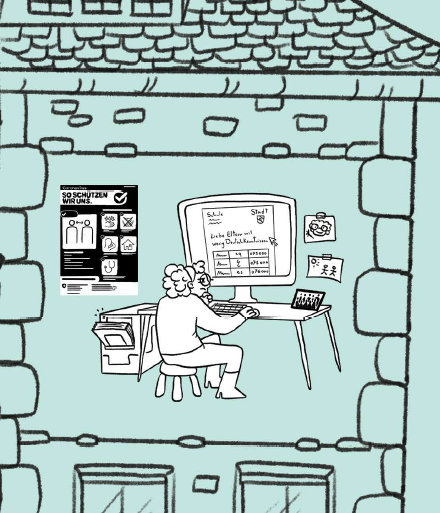

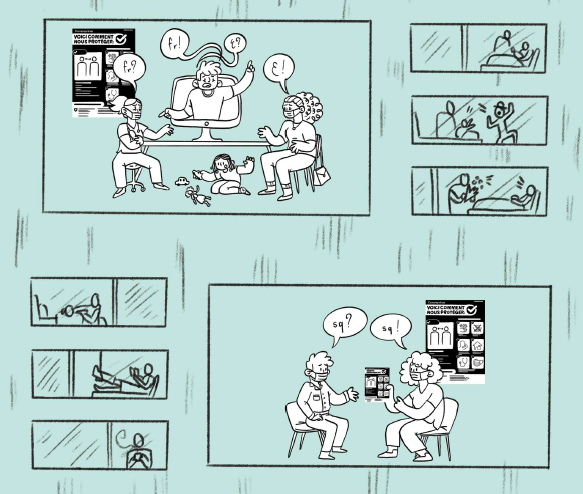

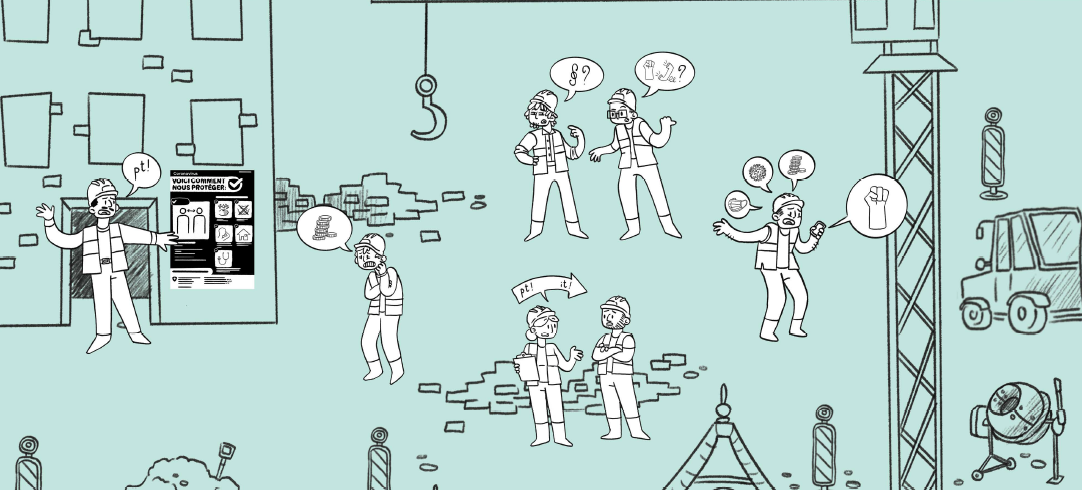

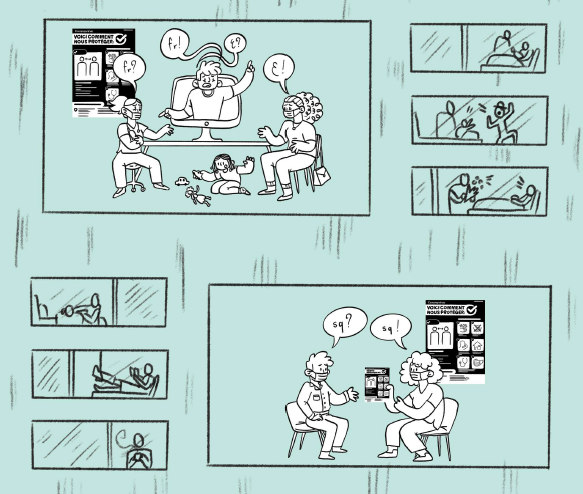

Self-employed translators who take on freelance assignments for the FOPH (Federal Office of Public Health) and other institutions in the health sector are inundated with work during the pandemic: their inboxes overflow with requests, deadlines are often unrealistic. In addition to the heavy workload and time pressure, the numerous changes that must be integrated immediately put major strains on translators. Not to mention the difficult conditions for those who are parents needing to temporarily home-school their children. Most language professionals keep their heads above water with lots of coffee and nerves of steel.

Independant translators

Self-employed translators who take on freelance assignments for the FOPH (Federal Office of Public Health) and other institutions in the health sector are inundated with work during the pandemic: their inboxes overflow with requests, deadlines are often unrealistic. In addition to the heavy workload and time pressure, the numerous changes that must be integrated immediately put major strains on translators. Not to mention the difficult conditions for those who are parents needing to temporarily home-school their children. Most language professionals keep their heads above water with lots of coffee and nerves of steel.

Independant translators

Self-employed translators who take on freelance assignments for the FOPH (Federal Office of Public Health) and other institutions in the health sector are inundated with work during the pandemic: their inboxes overflow with requests, deadlines are often unrealistic. In addition to the heavy workload and time pressure, the numerous changes that must be integrated immediately put major strains on translators. Not to mention the difficult conditions for those who are parents needing to temporarily home-school their children. Most language professionals keep their heads above water with lots of coffee and nerves of steel.

Translation agencies

Translation agencies providing services in numerous languages are in particularly high demand during the pandemic. To handle the workload, these agencies also contract freelance translators outside of Switzerland. Managing the projects is stressful, as finding someone on short notice to translate a document into Chinese, for example, can pose an impossible challenge. In addition, different holidays in different countries as well as different time zones further complicate coordinating assignments. And while the two-fold outsourcing procedure – first from governmental authorities and institutions to translation agencies, and then from the agencies to translators in Switzerland and abroad – ensures that translations into languages uncommon in Switzerland can be delivered quickly, outsourcing and internationalization also create additional market pressure on Swiss-based translators to keep their prices low and to work overtime to meet deadlines.

Southern Switzerland

The situation at the north entrance to the Gotthard Road Tunnel during the 2020 Easter holidays is nothing short of astonishing: instead of the normal scene with massive congestion and traffic backed up for kilometers, just a few cars are on the road – in addition to police officers distributing circulars in German, French, and Italian asking people not to travel to Ticino. Because no stay-at-home orders are issued in Switzerland, people are free to drive through the tunnel. Via posters and circulars, the Ticino government makes a public appeal for solidarity with the population in Switzerland’s southernmost canton, which is hugely impacted at the start of the pandemic. It’s a highly unusual request for a tourist destination. Well-known Ticino personalities are also active on (social) media in spreading the message.

Social work

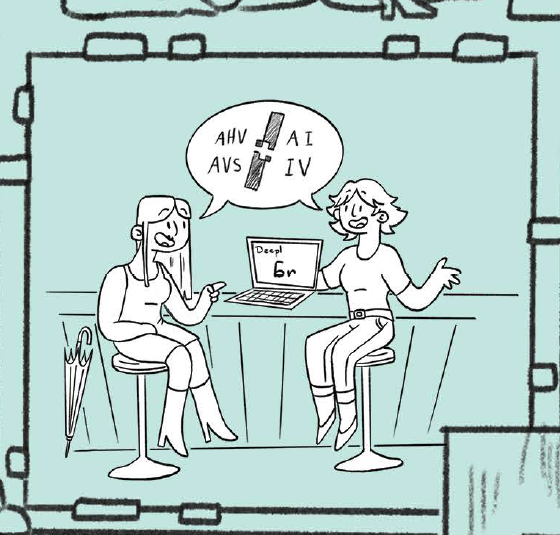

During the pandemic, several organisations are active in aiding particularly vulnerable populations, including sex workers. Part of this work is offering help with translating forms (e.g. compensation for loss of earnings), as sex workers who don’t speak a national language generally have problems with filling in forms written in French, German, or Italian. These translations (into Bulgarian, for example) are made using digital translation aids such as DeepL and used by social workers and other persons who are in direct contact with sex workers. The translations ensure that sex workers have access to vitally important material resources during the months of the pandemic when sex work is forbidden.

Social work

Many people involved in civil society organizations are proactive and seek contact to particularly vulnerable groups (migrants, sex workers, and unhoused people) to inform them about the coronavirus, preventive measures, and available aid. In addition, they distribute masks and hand sanitizer, and they explain how COVID-19 tests work. One such organization is a religious association that is particularly active on behalf of vulnerable groups during the pandemic. All these communication activities rely on the multilingual skills of volunteers, who often receive no compensation, as well as on automatic translation apps or other tools that enable successful communication.

Public broadcasters

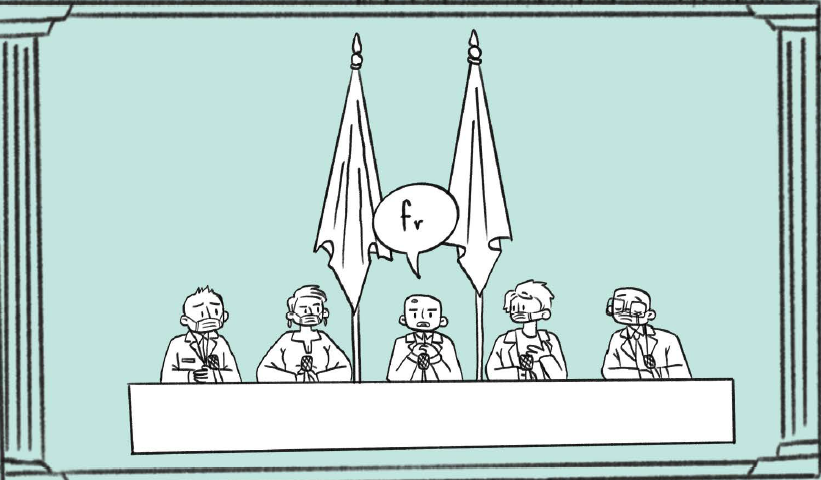

The public understandably has a great need for information in the early months of the pandemic. The media regularly report on the coronavirus and related measures adopted by government, while numbers and charts on COVID infections and deaths are omnipresent. Media professionals are also required to observe the preventive and social-distancing rules – for example, if wearing a mask hinders their work, they must conduct interviews using Plexiglas panels. Record numbers of viewers watch the Federal Council’s live press conferences held in the Federal Palace. The various public broadcasters hire interpreters to translate the press conferences into the local official language and into sign language; during the first few months of the pandemic, the Swiss Confederation assumes the costs for these services. People lacking skills in one of the official languages often seek information on other, foreign media channels, which causes some confusion as to which preventive and social-distancing rules are valid in Switzerland.

Diaspora media

The federal authorities fund several migrant-language diaspora media (audio and visual channels) to ensure they provide correct information on Switzerland’s official rules and measures. Diaspora media have a broad network of correspondents and translators from migrant communities who provide services in their first language for personal reasons and often for only symbolic remuneration.

Public broadcasters

The public understandably has a great need for information in the early months of the pandemic. The media regularly report on the coronavirus and related measures adopted by government, while numbers and charts on COVID infections and deaths are omnipresent. Media professionals are also required to observe the preventive and social-distancing rules – for example, if wearing a mask hinders their work, they must conduct interviews using Plexiglas panels. Record numbers of viewers watch the Federal Council’s live press conferences held in the Federal Palace. The various public broadcasters hire interpreters to translate the press conferences into the local official language and into sign language; during the first few months of the pandemic, the Swiss Confederation assumes the costs for these services. People lacking skills in one of the official languages often seek information on other, foreign media channels, which causes some confusion as to which preventive and social-distancing rules are valid in Switzerland.

Research and dissemination

Researchers are happy to meet again in person when universities re-open. In academia as in the general public, the pandemic is a much-discussed topic, and many research projects focus on the crisis. A team from the Research Centre on Multilingualism (RCM), assisted by the Scuola universitaria professionale della Svizzera italiana (SUPSI), conduct an investigation into multilingualism and related translation activities during the health crisis. Language barriers and other obstacles in addition to management strategies are studied. Their work sheds light on the fact that translation alone cannot mitigate the social inequities that have become more visible during the crisis.

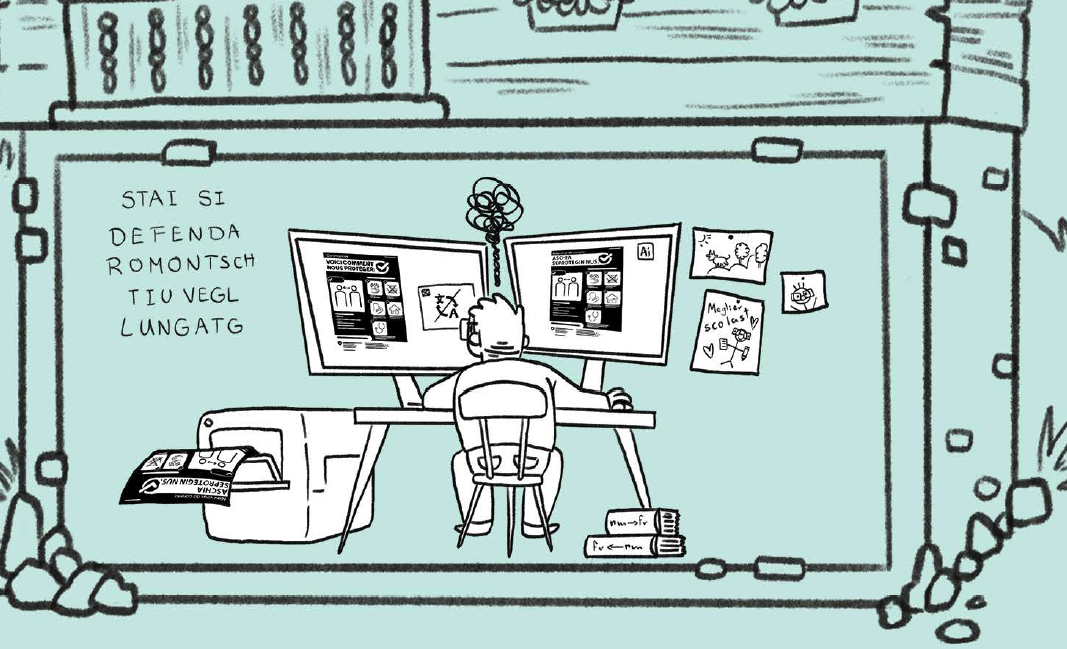

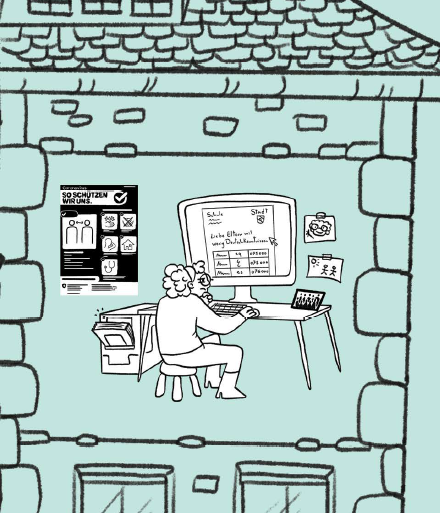

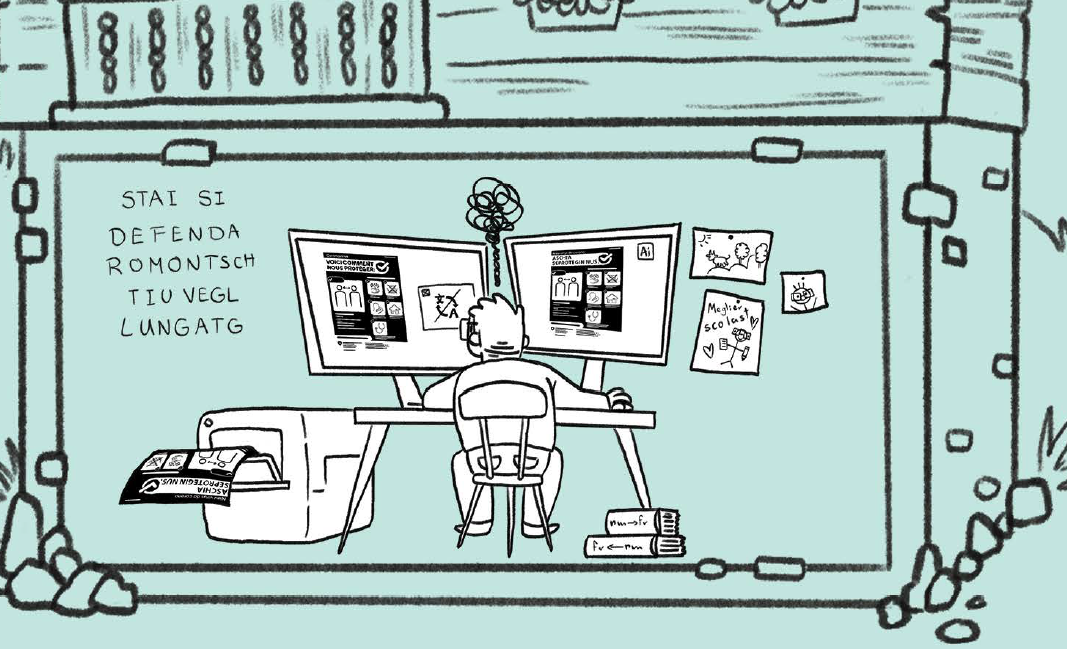

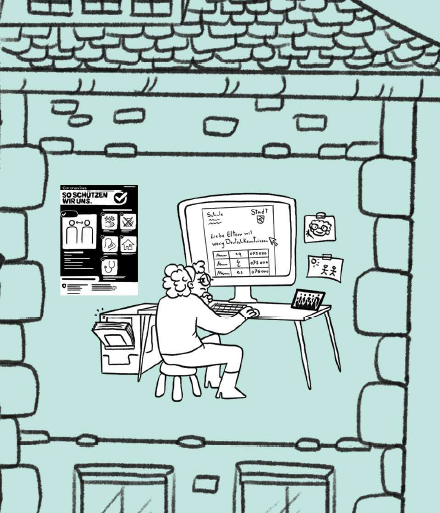

In the interest of ensuring easy access to the findings, the RCM-SUPSI researchers not only publish a report (available via QR-Code) but also work closely with a young artist to create illustrations depicting the topic. Talent, a sense of humour, and meticulous attention to detail guide him in his renderings of persons and places involved in mediating, translating, and interpreting during the pandemic.

School director

Schools are regularly confronted with situations that require translation. In part, they can rely on professional intercultural interpreters for parent-teacher conferences or other important meetings with people who don’t speak the language of schooling. Much more common, however, are situations in which teachers, parents or legal guardians, and children spontaneously take on the role of translator or interpreter. During the lockdown, everyone involved had to make the switch to distance learning – literally overnight – which brought about pedagogical and technical challenges. And, of course, language-related issues. One problem is that the language used in official communications is often complicated and very wordy. This motivates a school director to write a letter to make sure parents and guardians with limited German skills know who to call if they need help understanding the current rules and measures. She spares no effort in finding parents who speak the most common migrant languages at her school to ask them if they would be available as a contact person in case of questions. She appends a list with their names, telephone numbers, and languages to her letter.

Family members

Family members are often involved in translating for schools. For example, a father helps the school director translate a letter into Turkish. Although he grew up speaking Turkish in Switzerland, he rarely writes it, so he often needs to refer to a dictionary.

Older people

Older people with a migration background find the situation especially difficult. They don’t always understand the posters and circulars from the national coronavirus campaign, despite the use of pictographs. This causes confusion, as they’re unsure what they’re allowed to do – even whether they can leave their homes. Often relatives step in to help, as shown in the illustration where a boy translates the explanations under the pictographs into Tamil for his grandparent.

Intercultural mediators

Maintaining contact to families with a migration background is particularly important during the lockdown. For example, intercultural mediators bring toys and books to children, and they reassure families who haven’t left their home for days and who are too afraid of the coronavirus to open windows and let in some fresh air. The mediators explain – if necessary with their hands and feet – that Switzerland hasn’t issued a stay-at-home order and that it’s important for children to get outdoors and move.

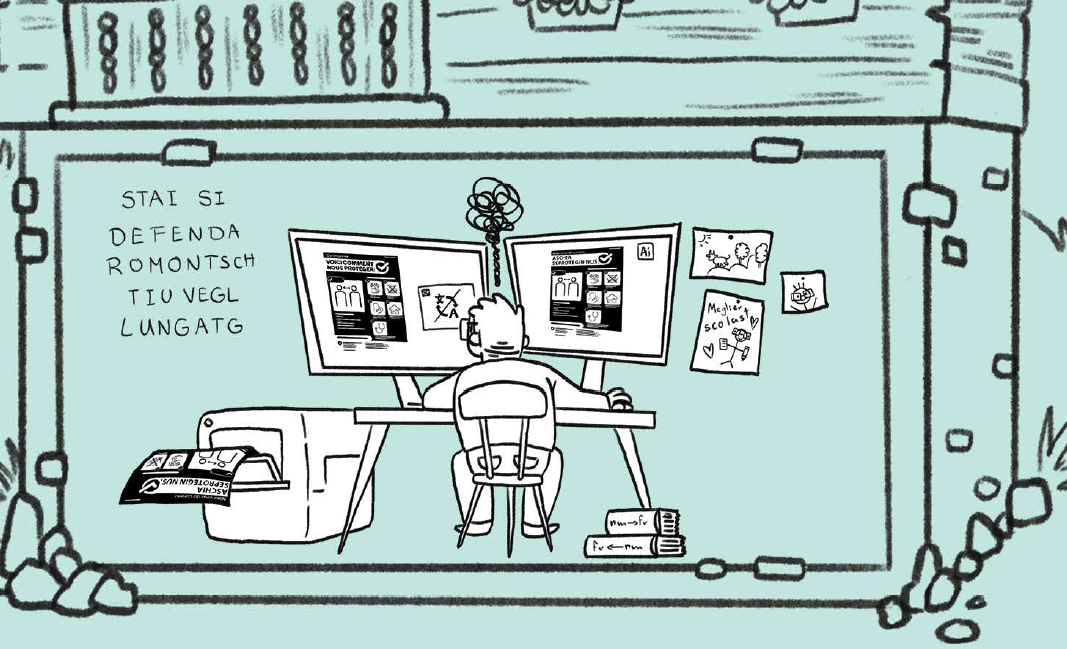

The translating teacher

At the very start of the pandemic, the hastily instituted FOPH coronavirus campaign provides no posters in Romansh. A teacher in Graubünden decides to take action himself. He produces a Romansh-language version using Adobe Illustrator, which he has used in the past for translating school-related information. Because there are no machine-translation programs for this language combination, he consults experts to find the right terminology. Although the FOPH soon provides a poster in Rumantsch Grischun, the teacher continues to produce a version of the most recently updated posters in the Surselvic idiom during the entire first year of the pandemic, as administrations and schools in neighbouring communes are very interested in posting the information in the local idiom.

Foreign national service offices

During the lockdown, officers in foreign national services work from home to provide migrants with multilingual information via social media channels and websites as well as by regular mail. After the lockdown, they return to their regular place of work where, at the welcome desk, the first step is often negotiating which language to use with clients. While it’s by no means unusual that both migrants and staff are multilingual, it’s not always possible to find a common language. These situations complicate even simple tasks like signing up for a language course or completing a form. Machine translation apps are often useful in translating basic information into languages like Tigrinya.

Multilingual hotlines

Some NGOs operate multilingual hotlines to ensure that people who don’t speak a national language have access to important information. These services also help migrants who have difficulty in finding official health and safety measures. Staff provide information about preventive measures, quarantine rules, and employment rights – and they also offer psychological support in uncertain times. These workers are rarely language professionals; their efforts supplement the information compiled and translated by the government.

Writing support office

Services offered in the writing support offices of numerous NGOs (the Red Cross, for example) represent a lifeline for people who lack skills in a national language or who have no access to services of governmental authorities. In these settings, staff at the NGOs as well as volunteers conduct written correspondence for the target groups and aid them in understanding and completing administrative tasks. Although NGO back offices remain closed during the pandemic, help is provided via other channels.

Organizations and associations

Several organizations and associations that are active in organizing regular events for migrant populations already before the pandemic continue their work during the crisis. Because in-person meetups are no longer possible, it’s essential to maintain contact with the target groups – also online – to prevent loneliness and address fears brought about by the situation. During the pandemic, associations that work for and with migrants to develop multilingual resources (moderation kits, for example) in order to provide targeted information about the pandemic. These initiatives are designed not only to ensure vulnerable individuals have social contact but also to provide answers to a wide range of questions, from health-related issues to worker rights.

Contact Tracing

Contact tracing is a central component of Switzerland’s strategy to slow the spread of the coronavirus. Here, too, translation services play a decisive role in ensuring that everyone – regardless of their language – receives the necessary information. Frequently, the persons involved in providing these services are not regularly employed – they’re often pensioners, unemployed individuals, or students who speak several languages but who aren’t professional translators or interpreters. These non-professionals repeatedly have to come up with new strategies to ensure their target groups understand the information, and they’re repeatedly confronted with topics that go beyond matters of public health. During the biggest waves of infections, hundreds of staff work the telephones. Because there are so many cases to process, contact tracers often work overtime. The contact tracing centres themselves are loud, and the working conditions are extremely stressful for many employees.

Healthcare sector

During the pandemic, issues surrounding translation are particularly urgent in the healthcare sector, including at hospitals, where an increasing number of interpreters work via digital communication channels like Zoom and similar platforms. Their main assignment is interpreting for migrants who don’t speak a national language or English.

Doctors and nurses from migrant populations, or those who maintain close ties with them, play a key role in this context: they inform communities about hygiene rules and encourage them to uphold safety measures. However, this crucial work also has a drawback: it potentially stigmatizes migrant communities if it causes the general impression that migrants are people who have difficulties in practicing good hygiene.

Unions

Unions are central players in supporting employees, and not only in times of crisis. During the pandemic, they set up multilingual hotlines to answer members’ questions about their legal rights and respond to existential concerns. Because some workers don't speak one of Switzerland’s national languages, it’s particularly important that union staff provide advice – which they do, not least thanks to their own linguistic competencies.To ensure they interpret and implement measures correctly, union staff are in constant contact with their legal departments, where the teams are responsible for gathering and preparing precise, case-specific information. Thanks to this flow of communication, workers receive advice quickly and are more or less able to come to terms with their situation.

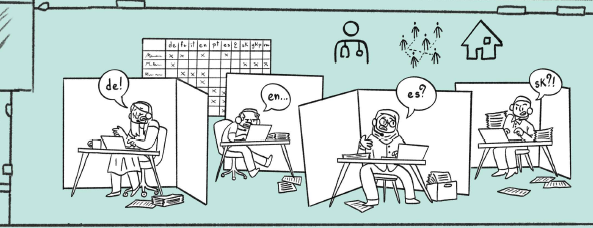

Construction industry

Working from home is naturally impossible in the construction industry. Important information about employment conditions and rights are available only in the official languages, which many construction workers don’t understand. The information gap (regarding employment contracts and wages, for example) has serious impacts, as the ever-changing legal bases and unclear rules cause confusion and raise fears. In such cases, non-professional translators – in other words, multilingual employees on site, staff at unions and non-governmental organizations - take on the role of translator.

Press conferences of the public administration

In addition to press releases, amended legal requirements must be made available in Switzerland’s three official languages and, if possible, in English for the press conferences held several times per week at the start of the pandemic. Some language services in the Federal Administration even set up on-call and weekend duty to ensure the translations can be delivered as quickly as possible. During press conferences, Federal Council members and experts speak in the official language of their choice. Because the interest in the press conferences is so large, they’re broadcast live and translated during the first months of the pandemic.

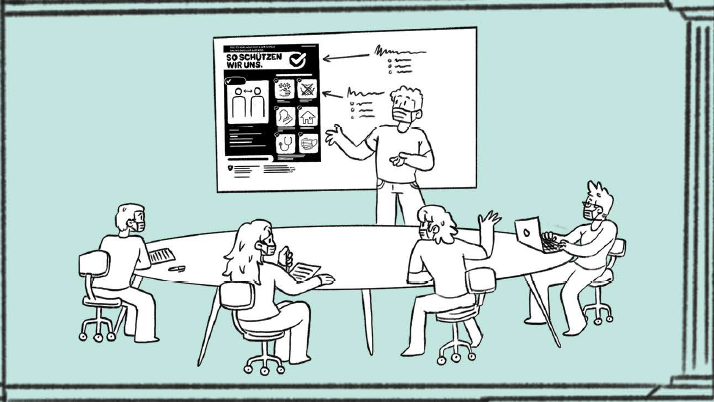

The FOPH campaigns

For the design of the materials, the FOPH campaign team and responsible communications agencies emphasize the importance of easily accessible pictographs and explanations. The continuously updated campaign materials are produced in German and then translated into the other national languages and English, in part into additional languages. The campaign motto “Protect yourself and others” studiously avoids threatening and prohibitory language; rather, it aims to influence public behaviors by addressing values such as solidarity, the common good and personal responsibility.

Communication tsunami

Maintaining physical distance, mask requirements, testing, contact tracing, isolation, quarantine, working from home, solidarity flags – these and other social distancing and hygiene rules are ubiquitous during the pandemic. Because the prolific information materials stem from various authorities and organizations, they sport different visual designs – and sometimes even have different content.

In the spirit of Switzerland’s decentralized, federalist tradition, the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) as well as individual cantons and cities launch their own coronavirus campaigns. In addition to the avalanche of official information, conspiracy theorists copy the visual design of the FOPH campaign to spread their messages. And because the situation is constantly evolving, new posters have to be put up regularly – obsolete posters left hanging cause additional confusion. In public spaces, the local official language is predominant, although other languages are also visible (at kiosks, for example, in flyering activities, or on windows of meeting places for migrant communities). At times, this “communications tsunami” via all channels, in various formats and languages, and from official and private organizations overwhelms the public – and not just people who lack skills in an official language.

Communication tsunami

Maintaining physical distance, mask requirements, testing, contact tracing, isolation, quarantine, working from home, solidarity flags – these and other social distancing and hygiene rules are ubiquitous during the pandemic. Because the prolific information materials stem from various authorities and organizations, they sport different visual designs – and sometimes even have different content. In the spirit of Switzerland’s decentralized, federalist tradition, the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) as well as individual cantons and cities launch their own coronavirus campaigns. In addition to the avalanche of official information, conspiracy theorists copy the visual design of the FOPH campaign to spread their messages. And because the situation is constantly evolving, new posters have to be put up regularly – obsolete posters left hanging cause additional confusion. In public spaces, the local official language is predominant, although other languages are also visible (at kiosks, for example, in flyering activities, or on windows of meeting places for migrant communities). At times, this “communications tsunami” via all channels, in various formats and languages, and from official and private organizations overwhelms the public – and not just people who lack skills in an official language.

Communication tsunami

Maintaining physical distance, mask requirements, testing, contact tracing, isolation, quarantine, working from home, solidarity flags – these and other social distancing and hygiene rules are ubiquitous during the pandemic. Because the prolific information materials stem from various authorities and organizations, they sport different visual designs – and sometimes even have different content. In the spirit of Switzerland’s decentralized, federalist tradition, the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) as well as individual cantons and cities launch their own coronavirus campaigns. In addition to the avalanche of official information, conspiracy theorists copy the visual design of the FOPH campaign to spread their messages. And because the situation is constantly evolving, new posters have to be put up regularly – obsolete posters left hanging cause additional confusion. In public spaces, the local official language is predominant, although other languages are also visible (at kiosks, for example, in flyering activities, or on windows of meeting places for migrant communities). At times, this “communications tsunami” via all channels, in various formats and languages, and from official and private organizations overwhelms the public – and not just people who lack skills in an official language.

Communication tsunami

Maintaining physical distance, mask requirements, testing, contact tracing, isolation, quarantine, working from home, solidarity flags – these and other social distancing and hygiene rules are ubiquitous during the pandemic. Because the prolific information materials stem from various authorities and organizations, they sport different visual designs – and sometimes even have different content. In the spirit of Switzerland’s decentralized, federalist tradition, the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) as well as individual cantons and cities launch their own coronavirus campaigns. In addition to the avalanche of official information, conspiracy theorists copy the visual design of the FOPH campaign to spread their messages. And because the situation is constantly evolving, new posters have to be put up regularly – obsolete posters left hanging cause additional confusion. In public spaces, the local official language is predominant, although other languages are also visible (at kiosks, for example, in flyering activities, or on windows of meeting places for migrant communities). At times, this “communications tsunami” via all channels, in various formats and languages, and from official and private organizations overwhelms the public – and not just people who lack skills in an official language.

Communication tsunami

Maintaining physical distance, mask requirements, testing, contact tracing, isolation, quarantine, working from home, solidarity flags – these and other social distancing and hygiene rules are ubiquitous during the pandemic. Because the prolific information materials stem from various authorities and organizations, they sport different visual designs – and sometimes even have different content. In the spirit of Switzerland’s decentralized, federalist tradition, the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) as well as individual cantons and cities launch their own coronavirus campaigns. In addition to the avalanche of official information, conspiracy theorists copy the visual design of the FOPH campaign to spread their messages. And because the situation is constantly evolving, new posters have to be put up regularly – obsolete posters left hanging cause additional confusion. In public spaces, the local official language is predominant, although other languages are also visible (at kiosks, for example, in flyering activities, or on windows of meeting places for migrant communities). At times, this “communications tsunami” via all channels, in various formats and languages, and from official and private organizations overwhelms the public – and not just people who lack skills in an official language.

Communication tsunami

Maintaining physical distance, mask requirements, testing, contact tracing, isolation, quarantine, working from home, solidarity flags – these and other social distancing and hygiene rules are ubiquitous during the pandemic. Because the prolific information materials stem from various authorities and organizations, they sport different visual designs – and sometimes even have different content. In the spirit of Switzerland’s decentralized, federalist tradition, the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) as well as individual cantons and cities launch their own coronavirus campaigns. In addition to the avalanche of official information, conspiracy theorists copy the visual design of the FOPH campaign to spread their messages. And because the situation is constantly evolving, new posters have to be put up regularly – obsolete posters left hanging cause additional confusion. In public spaces, the local official language is predominant, although other languages are also visible (at kiosks, for example, in flyering activities, or on windows of meeting places for migrant communities). At times, this “communications tsunami” via all channels, in various formats and languages, and from official and private organizations overwhelms the public – and not just people who lack skills in an official language.

Communication tsunami

Maintaining physical distance, mask requirements, testing, contact tracing, isolation, quarantine, working from home, solidarity flags – these and other social distancing and hygiene rules are ubiquitous during the pandemic. Because the prolific information materials stem from various authorities and organizations, they sport different visual designs – and sometimes even have different content. In the spirit of Switzerland’s decentralized, federalist tradition, the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) as well as individual cantons and cities launch their own coronavirus campaigns. In addition to the avalanche of official information, conspiracy theorists copy the visual design of the FOPH campaign to spread their messages. And because the situation is constantly evolving, new posters have to be put up regularly – obsolete posters left hanging cause additional confusion. In public spaces, the local official language is predominant, although other languages are also visible (at kiosks, for example, in flyering activities, or on windows of meeting places for migrant communities). At times, this “communications tsunami” via all channels, in various formats and languages, and from official and private organizations overwhelms the public – and not just people who lack skills in an official language.

Organizations and associations

Several organizations and associations that are active in organizing regular events for migrant populations already before the pandemic continue their work during the crisis. Because in-person meetups are no longer possible, it’s essential to maintain contact with the target groups – also online – to prevent loneliness and address fears brought about by the situation. During the pandemic, associations that work for and with migrants to develop multilingual resources (moderation kits, for example) in order to provide targeted information about the pandemic. These initiatives are designed not only to ensure vulnerable individuals have social contact but also to provide answers to a wide range of questions, from health-related issues to worker rights.

Interpreters in the health sector

The situation is also difficult for interpreters in the health sector. To avoid unnecessary exposure to the virus – but also to streamline processes and save costs – they increasingly work via video conferences, enabling them to interpret discussions between doctors and patients from their homes. However, technical problems and masks frequently impair communications. As a result, interpreters are often exhausted at the end of the workday.

Independant translators

Self-employed translators who take on freelance assignments for the FOPH (Federal Office of Public Health) and other institutions in the health sector are inundated with work during the pandemic: their inboxes overflow with requests, deadlines are often unrealistic. In addition to the heavy workload and time pressure, the numerous changes that must be integrated immediately put major strains on translators. Not to mention the difficult conditions for those who are parents needing to temporarily home-school their children. Most language professionals keep their heads above water with lots of coffee and nerves of steel.